Canadian Presbyterian, Methodist and

Congregational Church

Music Prior to 1925

The full text of this article is copyright © 1995 by Bruce

Reginald Harding

excerpted from

Presbyterian, Methodist and

Congregational Worship in Canada to 1925

by Thomas Harding and Bruce Harding (Toronto: Evensong, 1995)

Copies may be ordered from Evensong

Worship Resources

Metrical Psalters in English, Early Psalm Tunes

The Calvinist leanings of early English and Scottish Protestants resulted in a virtual ban on hymn texts of human composition. Psalms and scripture canticles were considered the only worthy vehicles of church praise. Following the lead of the French court poet Clément Marot, Thomas Sternhold, royal groom to Henry VIII and Edward VI began creating metrical translations of the psalms in the 1540s, in a 14-syllable metre subdivided into eight syllables followed by six. (1) Many more metrical translations were written on the continent during the Marian exile (1554-58) and the first official complete metrical psalter in English, the Whole Booke of Psalmes, was published by John Day in 1562. This collection came to be known as Sternhold and Hopkins, after the principal contributors.In Scotland the poetic merits of Sternhold and Hopkins were questioned almost immediately, leading to the eventual adoption of the Psalms of David in Metre (1650; known thereafter as the Scottish Psalter), an adaptation of a metrical translation by Francis Rouse. The Whole Booke of Psalmes remained in use in England, however, until a royally-sanctioned publication by Nahum Tate and Thomas Brady, the New Version of the Psalms of David (1696), began to gain in popularity. Sternhold and Hopkins became known as the Old Version, Tate and Brady as the New. (2)

As with the origin of the common metre in the early metrical psalm translations, the origins of the early psalm tunes remain obscure. (3) The tune collections issued in England by Este (1592) and Ravenscroft (1621) were very influential, and a common corpus of tunes soon developed. In Scotland, through the course of various psalters with tunes appended in 1615, 1625 and 1635, a set of common tunes became canonized. The twelve tunes of 1615 were: OLDE COMMON TUNE (known as OXFORD in England), KINGES TUNE, DUKES TUNE, ENGLISH TUNE (LOW DUTCH or CANTERBURY), FRENCH TUNE, LONDON TUNE (CAMBRIDGE), THE STILT (YORK), DUNFERMLING TUNE, DUNDIE TUNE (WINDSOR), ABBAY TUNE, GLASGOW TUNE and MARTYRS TUNE. All but one of these continued in common use in Presbyterian churches until the mid-19th century (4) and six are still included in hymn collections today. (5) Other important tunes appeared in successive psalters. For ELGIN in 1625 and WINCHESTER (now WINCHESTER OLD) in 1635.

A collection of tunes issued in Massachusetts in 1698 sheds light on what was in common use among the Puritans (or Congregationalists as their descendants later came to be known) of New England. (6) Earlier, also in response to the perceived deficiencies of Sternhold and Hopkins, a new translation of the psalms had been compiled and issued by the Puritans, the Bay Psalm Book (1640). The 1698 edition included an appendix of tunes which the compilers considered suitable for use: OXFORD, LITCHFIELD, LOW DUTCH, YORK, WINDSOR, CAMBRIDGE SHORT (a 6686 version of LONDON), ST. DAVID'S, MARTYRS, HACKNEY (ST. MARY'S), 119TH PSALM TUNE SECOND METER, PSALM 100 FIRST METER (OLD 100TH), PSALM 115 FIRST METER (OLD 113TH) (7) and PSALM 148 FIRST METER. (8) This list taken together with the twelve Scottish tunes of 1615 establishes a relatively well-defined picture of the tunes in common use in the Old World and the New in the latter half of the 17th century. (9)

The Old Way of Singing, Lining Out

By the mid-17th century a style of unison, unaccompanied singing of the psalms without leadership had evolved in dissenting churches. This style was known as "the Old Way of Singing" or the "Common" or "Usual" way. (10) An extremely slow pace gradually became the norm. As late as 1787 a whole note in psalm singing was defined as being "as long as one can conveniently sing without breathing." (11) More adventurous precentors and members of the congregation would amuse themselves by ornamenting or "gracing" held notes. In time, individual congregations would often have completely different versions of the same melody! (12)The Old Way of Singing was further complicated by the practice of "lining out" the psalms, first adopted by the Westminster Assembly in 1644:

Over time, what was clearly intended as a temporary measure became a hallowed tradition, especially associated with Scotland. (14) Millar Patrick has described the qualifications necessary for a psalm leader or precentor:

Precentors eventually became men of considerable power in both church and community, with their own desk in front of or beside the pulpit, although usually not as high. Both the Old Way of Singing and the practice of lining out the psalms continued until the emergence of the Regular Singing movement in the 18th century.

Regular Singing, the Singing School Movement and Fuging Tunes

Around 1720 a group of New England Congregationalists, following the lead of their Independent counterparts in London, began to call for a change in sacred music. The "Regular Singing" movement, as it came to be known, advocated singing psalms according to the rules of the Gamut, teaching people to read musical notation rather than singing by ear. (16) Singing schools were gradually introduced throughout the American colonies, often conducted on a temporary basis by itinerant musicians. Such schools typically met two or three evenings a week for a four to six week period, culminating in a final concert to display what had been learned. After mid-century, many tunebooks were published, often by the singing school instructors themselves.Tunebooks invariably began with an instructional preface outlining the rudiments of music, followed by an often quite personal selection of psalm tunes harmonized in two to four parts. A selection of longer pieces (anthems) was usually included at the end for more advanced learning. By 1775 even rural areas were being influenced by this movement. (17) Eventually most congregations had a song leader with some degree of musical training, and instruments such as the bassoon and the bass viol (the Presbyterian "kirk fiddle") were often employed to keep the singers on pitch.

The original intent of the singing school movement was the enhancement of congregational psalmody. Soon, however, these groups became more elitist, demanding more challenging, elaborate music. (18) Hence the development of the fuging tune.

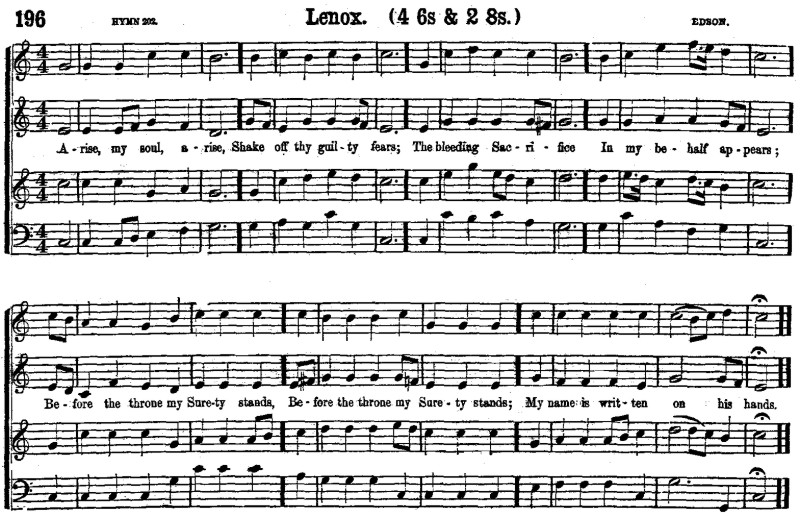

Temperley has shown that fuging tunes

evolved first in English Anglican parishes without organs,

and spread from there to Congregationalist and Baptist congregations in

England and North America. (19) A

tune is defined as fuging if, "in at least one phrase, two or more

voice parts enter non-simultaneously, with

rests preceding at least one entry, in such a way as to produce overlap

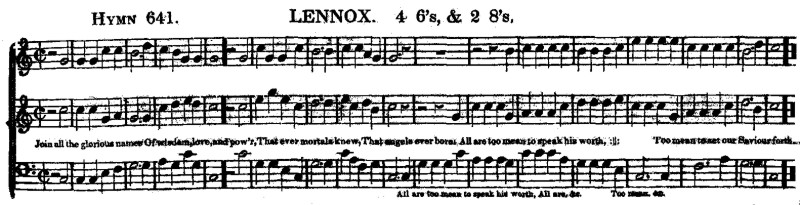

of text." (20) LENNOX (Example 1) was,

according to Richard Crawford, the most frequently reprinted

American fuging tune. (21) A simple

pentatonic melody suggests folk influence, five-measure phrases reveal

a link to the gathering-note tradition of psalm singing, and the

counterpoint in the fuging section is

repetitive and static:

Example 1: LENNOX,

from Sacred Harmony (Toronto,

1838)

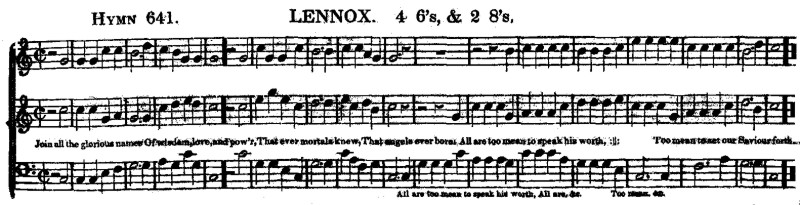

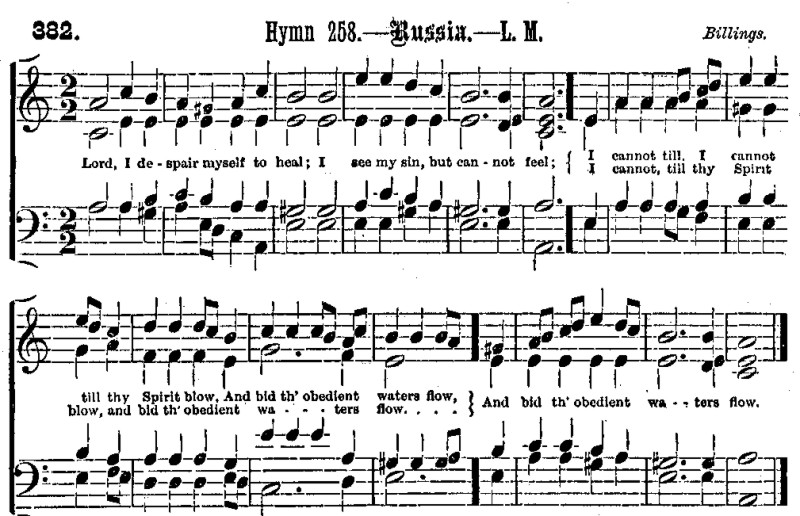

Another popular tune, RUSSIA (Example

2), shares many features with LENOX. Here

a sequence involving parallel octaves between the tenor and bass

provides the foundation for the fuging

section:

Fuging tunes reached their peak in popularity between 1760 and 1800, both in England and America, after which time a new reform movement caused a decline in their use. They continued to appear in tune collections until the late 19th century, however. (22)

The Expansion of Psalmody: Isaac Watts and the Scottish Paraphrases

Isaac Watts (1674-1748) has long been considered the "Father of English Hymnody." Before Watts, hymns played an insignificant role in worship, but he publication of Hymns and Spiritual Songs in 1707 sparked a revolution in English hymnody. During the next hundred years, Watts' hymns were almost universally accepted in the Independent churches, the Wesleys followed Watt's lead in making hymns a central part of Methodist worship, and hymns eventually gained equal footing with the psalms in Anglican worship. Hymns by Watts such as "Jesus shall reign where'er the sun" and "When I survey the wondrous cross" have become a treasured part of our musical heritage.Watt's hymns were not the only influential part of his creative output, however. Like others before him, Watts felt that the psalms did not adequately express the Christian ethos:

Watts' The psalms of David imitated in the language of the New Testament was published in 1719. The two books together became known as Psalms and Hymns, and continued to influence Congregational psalmody until well into the 19th century.

By the mid-1700s, Watts' Psalms and Hymns were also circulating widely in Scotland, instigating a call for an official Presbyterian collection of hymns and scriptural paraphrases. An overture to the General Assembly in 1741 led to the publication in 1745 of a small collection of Translations and Paraphrases for the consideration of individual presbyteries. (24) No official sanction was given to this collection, however, since presbyteries chose not to respond. The matter remained unresolved until the publication of another Translation and Paraphrases in 1781. (25) This collection was authorized for use "in the meantime" while presbyteries were considering it. (26) Although no final decision was ever reached, the collection was gradually adopted in many Presbyterian churches, opening the door for the eventual acceptance of hymns during the 19th century.

Methodist Hymnody

Methodism was born during the 18th century musical revolution created by the Regular Singing movement. John Wesley did not like the Old Way of Singing, remarking in Select hymns with tunes annext that "this drawling way naturally steals on all who are lazy." (27) However, neither did he like the elaborate Anglican choral tradition of his day, a tradition that had taken music out of the hands of the people and placed it in the hands of professionals. (28) Wesley's ideal was the singing of the Moravian Brethren he first heard during his ocean crossing to America in 1735, communal singing involving simple chorale melodies.Charles Wesley wrote over 5,500 hymns while John Wesley worked as a translator of hymns (at least 30 from the German), editor and compilor. Within a generation Methodists became known both in Britain and America for their singing, to such a degree that the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote in 1760: "Something must be done to put our psalmody on a better footing. The Sectarists gain a multitude of followers by their better singing." (29) During the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774, John Adams wrote of his visit to a Methodist meeting: "The singing here is very sweet and soft indeed; the first [finest] music I have heard in any society, except the Moravian, and once at church with organ." (30)

The thousands of hymns written and compiled by the Wesleys were sung to a variety of music. The old psalm tunes continued to be used (many Wesleyan hymns were written in common metre to facilitate singing with already familiar tunes), but a new corpus of music also emerged, one that reflects the mileau of the 18th century. The major tune sources are A Collection of Tunes Set to Music as They are Commonly Sung at the Foundery (1742), Hymns for the Great Festivals (1746), (31) and Select hymns with tunes annext (1761). (32) Temperley has given a good description of the 18th-century Methodist style of tune:

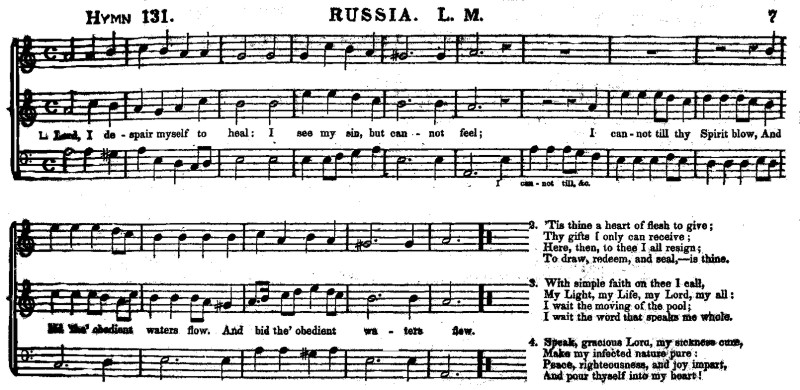

The ornate character of many

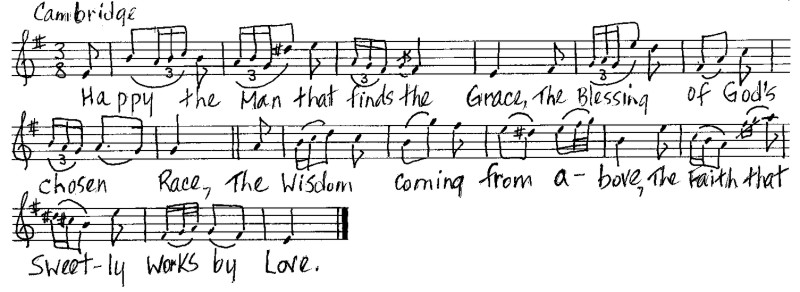

Methodist tunes is quite striking. CAMBRIDGE (Example 3; not the

same as the psalm tune CAMBRIDGE) has a rather unvocal melody, with

wide-ranging leaps and many

ornaments.

Example 3:

CAMBRIDGE, from Select hymns with

tunes annext (London, 1761)

SALISBURY remains in use today, in a

slightly modified form, as EASTER HYMN (Hymnary

105). FRANKFORT is a 3/4 time version of the modern WINCHESTER NEW (Hymnary

16). A slightly

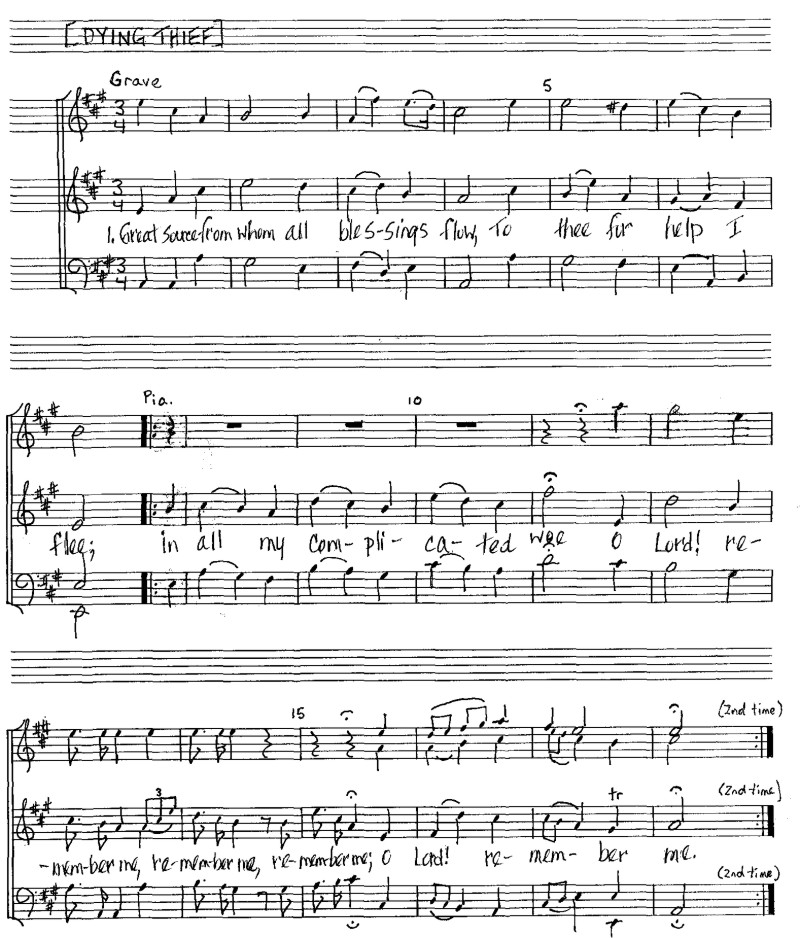

later tune, DYING THIEF (Example 4), began appearing in Methodist

collections around 1800 (known

today as RICHMOND [Hymnary 14]).

Example 4: DYING

THIEF, from Union Harmony,

2nd ed. (St. John NB, 1816)

The antiphonal contrasts and Italian operatic idiom are quite

clear,

especially in the phrase which is no longer sung, measures 11-15. Other

tunes which survive today, often

in simplified form, include: DERBE (Hymnary 573), HELMSLEY (Hymn

Book [1971] 393), LEONI

(Hymnary 25), MORNING HYMN (529), MOSCOW (240), OLD 23RD

(272), ST. BRIDE (265) and

SAVANNAH (292).

Even in Select hymns with tunes annext, which is essentially Wesley's attempt to simplify congregational singing, the art music influence is clear. In the section "The Gamut, or Scale of Music," instructions for ornamentation are given:

Following these instructions the amount of ornamentation would be significant, with trills in virtually every phrase. Overall, Methodist music of the period is sophisticated, requiring a fair amount of musical ability to perform.

North American Singing Style, the Development of "Scientific Music"

Early 19th century sources portray a rather interesting picture of singing in North America. In 1846 The Bangor [Maine] Billings and Holden Society was organized to revive "old-fashioned singing." (35) A reviewer in the Boston Courier praised the style of singing evidenced at the Society's first concert, "which was quite different from that of the present day throughout.... I was happy to find that the rich nasal sound of forty years ago is not yet forgotten, and that the practice of beating time with the hand still exists." The reviewer was particularly pleased with the "strong voices and peculiar intonations" of the Bangor ladies. (36)A similar style of singing is suggested by Jane Hopper's recollection of her Primitive Methodist mother's singing of the tune BALERMA (Hymnary 180): "[It] was like no tune on earth; full of all kinds of little wailing bars, going from the minor to the major scale at any moment; but her voice always trembled at the word 'trembling,' and seemed to go down hill a couple of times to the end of the verse. She invariably sang it the same way, queer as it was...." (37) Although this latter description could be of a very personal interpretation, the possibility exists that this style of singing had been learned in a congregational setting.

Finally, a set of "Ironical Rules for

Singing at Church" was published in the Portland Advocate:

1. A man who sings at Church, should always in so doing, make a noise as loud as common thunder, and not bury his talents in a napkin; the more of a good thing the better.

2. If he sings tenor, he should always sing through his nose as well as his mouth; he takes wind in at both passages, and why not send it out at both?

3. The nasal twang is so much the better, because it resembles the hautboy stop on the organ.

4. Besides it is doing equal and exact justice, to make the mouth and the nose both officiate at the same time.

5. If he sings bass let him sing it with a vengeance, and if he cannot sing right, let him sing wrong; but by all events put his shoulder to the work.

6. He should never trouble himself about correctly pronouncing the words of the psalm, or hymn, 'words are but wind,' and not only so, who can pronounce the words with his nose!

7. But if the singer chooses to pronounce

the words, he should do it with a flourish and a sort of whirlwind in

the

mouth; in this manner they become magnified and circumvolved and

beautifully confused; there is no danger in all

this; for they will all get into perfect order again by the time they

have travelled once around the meeting house. (38)

The tunes and harmonisations of American composers such as Billings and Holden were considered crude; and, in a purely technical sense they were--full of parallel fifths and octaves, often solely pentatonic, with little sense of harmonic movement and many chords lacking thirds, etc. These were not highly trained composers but practical people who saw a need for church music and filled it, learning musical skills as they went along. The popularity of such indigenous American music was being questioned, however. Many American composers began to look to European musical fashions and European music theory as an alternative. Simple tunes such as OLD 100TH were held up as "ancient music"--examples of the best in church music--and new tunes were written with similar aesthetics in mind. The tide was turning, and European tunes and musical styles began to dominate American tunebooks. (39)

The most famous proponent of this reform was Lowell Mason, a Boston educator and musician. Mason's work as a tunebook compiler and writer about music was phenomenally influential. (40) By the 1850s, virtually all church music published in America bore the mark of the Mason school. The term "scientific music" became widely used in church music circles to denote well-constructed music (meaning music written by educated musicians). Whether strictly appropriate or not, titles such as "Professor" came to be commonly used by musicians. The movement led to the virtual extinction of American folk hymnody and a legacy of tunes adapted from European chant and art music, such as ANTIOCH (Hymnary 55), HAMBURG (208) and original tunes such as Mason's ARIEL (43) and BETHANY (321).

Presbyterian Church Music in Canada

Presbyterians emigrating from the American colonies or from Scotland and England brought with them their beloved psalm tunes and the practice of lining out. The diary of Ely Plater of York for Sunday, 23 January 1803, reads:

...after Dinr. was over, the Girls wishing to go to meeting which was

to be holden in the eveng at Mr. Cooper we

started in both Sley's and got down in good time the Minister was of

the Church of Scotland and gave us a very good

discourse--there was three psalms sung the two last was sung by Mr.

Ward in which Mr. Hewd & me assisted

him.... (41)

The 19th century would see significant developments in Presbyterian "church praise," however, including the introduction of instruments (fifes, flageolets and the "kirk fiddle") and church choirs, an expanding repertoire of psalm tunes, and eventually the introduction of hymnody and the organ.

American singing school masters were a part of Canadian life from the beginning, though at first only tentatively. One of the earliest was James Lyon, a Presbyterian minister from Princeton who arrived in Halifax in 1765 to serve the dissenting congregation there, moving on to Onslow Township a year later and finally to the Pictou area in 1768. Prior to his ordination Lyon had been active as a singing school master and had published a tunebook, Urania, in Philadelphia in 1761. It is likely that he brought copies of this book with him to Nova Scotia and used it in worship there. Lyon was eventually called to the pulpit at Machias, a settlement on the coast of Maine, in 1772. (42)

Like the later Canadian tunebooks published from 1801 until mid-century, Urania was produced in the American oblong-octavo open-score format, often called "longboy," with the melody in the tenor voice. (43) Only four of the 70 psalm tunes in the book are still in use today: ST. ANN'S (Hymnary 409), OLD 100TH, LONDON NEW (646), and HANOVER (21) which Lyon designates as "The 149th Psalm Tune." Others were well-known tunes of the time, including WINDSOR, WESTMINSTER (not the WESTMINSTER of today) and WELLS.

Urania includes 12 anthems and closes with 14 hymn tunes with full texts underlaid (placing these last reflects the relative novelty of the hymn genre). Two of these hymn tunes are in use today: SALISBURY and the tune for "God save the Queen" (which Lyon refers to as "Whitefield's"). All 14 appear to be of 18th-century origin, many of them from the collection Harmonia Sacra (c.1760). (44) The inclusion of hymn tunes in a collection published by a Presbyterian is explained in Lyon's preface addressed "To The Clergy of every Denomination in America." (45) As the title page indicates, the volume is "peculiarly adapted to the use of Churches and Private Families," this latter intention providing Lyon with the excuse to include hymns. (46)

For Presbyterians, the metrical psalms

were virtually sacred texts. Evidence of this is found in the curious

Scottish custom of writing practice verses to learn the psalm tunes,

thereby saving the actual psalm texts

for the sanctity of worship. The earliest surviving Canadian tunebook

is actually a small handwritten

volume of this type, dated 1813. (47)

The book contains 12 tunes written in elaborate letter notation:

FRENCH, LONDON, YORK, DUNDEE, ELGIN, DUBLIN (or IRISH [Hymnary

138]), ABBEY,

MARTYR'S, DAVIDS, NEWTON, MARYS and SAVOY (actually OLD 100TH). Each is

accompanied

by a short verse such as the following under MARTYR'S:

A snowey breast a sparkling eye

I never will admire

But she thats Blest can make me chaste

And with her I'll retire.

Aside from its delightful texts, this little book is invaluable for the evidence it provides concerning psalm tunes and educational practice in Upper Canada in the early 19th century. The notation itself demonstrates that alternative methods of music teaching were in use. Not surprisingly, most of the tunes are those of the 1615 Scottish Psalter. (48)

Despite the best efforts of singing school masters, early 19th century Presbyterian singing could be quite dismal. One commentator wrote of a service in St. Catherines ON:

Despite its critical tone, this description (written by a visitor from Scotland with a poor opinion of the colonies) provides important information on Presbyterian musical practices in Upper Canada in the 1820s. Note the presence of a gallery choir, the use of instruments, and the (seeming) lack of singing by the congregation.

That Presbyterian churches in British North America were in a time of musical transition is noted by William Lyon MacKenzie.

At issue was the "Scots version of the

Psalms and Paraphrases" versus the "Psalms of Dr. [Isaac] Watts."

Referring to the (secessionist) Presbyterian Church of York, Mackenzie

wrote in the Colonial Advocate

(December 22, 1825):

We

could wish, as this is the only Presbyterian Church in or near York,

that the Scots version of the Psalms and

Paraphrases were used during one part of the day and the Psalms of Dr.

Watts' on the other. The Americans and

English prefer the latter, the Scotch, and perhaps the Protestants from

the north of Ireland the former.... As we are

met here from various parts of the globe we respectfully submit to our

elders whether it would not be advisable to

introduce not only the versions but also the tunes which the

presbyterian in America as well as in Scotland and

Ireland are best accustomed to.

A letter to the editor published in

the Advocate in 1828 was even more pronounced in tone:

Our

greatest annoyance arose from the tunes and psalmody:--[The tunes

produce a fine stage effect, but being removed ninety

degrees from the sweet and simple melodies in use in Europe, the

congregation can no more join in singing "to the praise and

glory of God" than if they were deaf and dumb. The old and solemn tunes

of other years are laid aside to make way for airs

better fitted for the playhouse than a presbyterian reformed

congregation; and the substitution of Watt's independent version

of the psalms in use in the north of Ireland and Scotland, compleats

our musical misfortunes, and makes us feel as if in a

strange land. The associations connected with the psalms we have oft

sung and learnt by heart in our earlier and happier years

can never be effaced by a more harmonious version, even if accompanied

by a band, a fife, and new tune as uncouth as if

newly imported from Italy by Madame Catalani.]-- At last however the

singers struck up Coleshill, and altho the independent

psalmody was continued, the change was, on the whole, for the better. (50)

Watts' psalms were adopted by many of the more liberal Presbyterian congregations, both in the New World and the Old. This conservative versus liberal debate concerning texts, tunes and the use of instruments in worship would haunt the Presbyterian churches in Canada for years to come, however, eventually leading to bitter battles within the church courts.

Although instruments were in relatively common use in Canadian Presbyterian churches from early in the 19th century, organs did not appear until mid-century. The high cost of pipe organ manufacture had kept them out of all but the largest churches, and even then predominantly in those with liberal American membership. (51) By mid-century, however, rapid technological advances made possible the production of low-cost reed organs. (52) Suddenly, organs were available to small congregations throughout North America.

Frederick Rennie cites the installation of an organ in First Presbyterian, Brockville ON in 1855 as the critical moment in what came to be called "the great organ controversy." (53) The Synod declared:

Two years later the Brockville Church finally complied with this order. (55) In 1860 the Synod ordered the Session of St. Andrew's Church, Toronto, to remove their organ from the sanctuary. The Session refused to comply, however, and the debate continued for almost 20 years with pamphlets and church periodicals taking sides in the dispute. (56) A central issue in the controversy was the aid rendered to congregational singing by the support of an organ versus the silencing of congregational praise in favour of professional musical performance. (57) Eventually the General Assembly of the Canada Presbyterian Church opted, in 1872, to allow individual congregations to decide for themselves. (58) Gradually organs were introduced throughout the country. (59)

Antipathy to hymns in Canadian

Presbyterian churches was often as strong as the opposition to organs.

Officially Canadian Presbyterian church praise included only the psalms

and paraphrases, until events in

Scotland began to affect the Canadian scene. In 1851 the Hymn Book

of the United Presbyterian Church

was published in Scotland, sparking a controversy in Canada. (60) The conservative Ecclesiastical

and

Missionary Record trumpeted a warning:

Several sections of the visible Church use, in the worship of God,

hymns of mere human authority.... One of the first

steps in the defection of those churches which have departed from the

faith once delivered to the saints, has been

the superseding of the words of the Holy Ghost and substituting the

words of man in the worship of God. There is

cause for alarm, for the purity and stability of the Church, that

disregards scriptural worship. (61)

The Canadian Presbyter, on the other hand, called for a Free Church hymn book, specifically mentioning the merits of the United Presbyterian book. Since hymns and hymn collections were already in use in some congregations, the Presbyter argued that those of poor quality could be avoided by introducing a standard Canadian collection. (62) Two Canadian volumes were issued in the 1860s, Hymns for the Use of Sabbath Schools in Connection with the Canada Presbyterian Church (1862) and Hymns for the Worship of God (1863). The definitive collection was not issued until after the union of 1875, however: the Hymnal of the Presbyterian Church in Canada (1880).

The 1890s and early 1900s saw the rapid development of music within the Presbyterian Church in Canada. The most important single influence was that of Alexander MacMillan. (63) Coming from Edinburgh to serve mission fields in Manitoba and the Northwest in 1885, MacMillan returned to Canada permanently in 1887. In 1892 he was appointed to the committee charged with revising the 1880 hymn book. The appointment suited MacMillan well, allowing him to pursue his interests in music and worship, subjects he had studied in Edinburgh. A call to participate in a joint hymn book project proposed by the three Presbyterian Churches of Scotland resulted in MacMillan and Daniel J. Macdonnell, chair of the music subcommittee, being sent as Canadian delegates in 1894. Macdonnell's untimely death from pneumonia left MacMillan as the sole Canadian representative. When he returned to Canada, still only 30 years of age, MacMillan was appointed Macdonnell's successor.

Despite all the effort put into the join hymn book project, the Canadian church ultimately rejected the first draft due to a lack of selections from the paraphrases and lack of evangelistic hymns. Instead a Canadian volume was issued in 1897, the Presbyterian Book of Praise. MacMillan continued his work on hymnody for the rest of his life, eventually becoming full-time secretary of the Committee on Church Praise, 1914-1925, and continuing in a similar capacity in The United Church of Canada after union. (64)

Methodist Church Music in Canada

Methodism and music have always been intertwined in popular understanding. Hymn singing continued to be a support for many Methodists as they laboured to build a new life in a strange land. During the heyday of Canadian Methodism, one observer noted: What

has made the Methodist Church the most extensive of all denominations?

Because it surpassed all others in

heartiness of singing. The Methodists all sing. I have travelled up and

down the land, I have seen many strange and

curious things, but I never yet saw a Methodist that could not sing.

They sing with their throats. They sing with their

hands. They sing with their feet. Set a Methodist man and his wife down

in the middle of a Western prairie, and they

begin to sing; and in a short time on one side of them comes up a

meeting-house, and they keep singing until up

comes a whole conference. (65)

Music was truly the heart and soul of Methodism, carrying it through the pioneering years and into the modern age. (66)

One of the first singing school master to permanently immigrate to the British North American colonies was Stephen Humbert. Humbert founded the first Methodist congregation in St. John NB in 1791, established a singing school (announced in the St. John Gazzetter and Weekly Advertiser, November 11, 1796), and published Canada's first English-language book of music, Union Harmony, in 1801. The printing of three subsequent editions (1816, 1832, 1840) testifies to the popularity of Humbert's book. (67)

Similar to Lyon's Urania in

a number of ways--longboy format, with theoretical introduction,

etc.--Union Harmony had one significant additional feature.

Though the fuging tune was fading in

popularity south of the border, out of 229 selections in the second

edition (1816) of Union Harmony, 89

are fuging tunes (over a third of the volume). Humbert devoted a

considerable portion of the preface or

"Advertisement" to a defense of the genre:

Objections have been made by some compilers of devotional musick

against the use of fugueing tunes in divine

worship. It is allowed that injudicious performers have abused that

species of composition through ignorance in the

performance of good musick, and the introduction and too frequent use

of fugueing tunes not properly composed

for the solemnities of worship. But it is nevertheless believed that

fugueing musick, when judiciously performed,

will produce the most happy effect, without the least disorder of

jargon, especially when it is considered we do not

sing to please men, but the Lord. If those who are hearers, while others are performing

that part of divine worship,

were as assiduous to learn Sacred Musick, as they too generally are the

giddy amusements of the day, we should

have less hearers and more performers of this animating part of divine

worship; and whole assemblies might join

to confess how amiable and pleasant it is to "Sing unto the Lord with

the spirit and with the understanding also."

The popularity of Union Harmony suggests that Humbert knew his market well (New Brunswick and Nova Scotia being perhaps a bit "behind the times" in terms of congregational singing style and repertoire in the early 1800s). There is also evidence in the same edition of British Wesleyan influence as well. (68) Selections 200 to 213 are quite different musically from the other pieces in the book, bearing the musical stamp of the English Wesleyan style and probably being derived from an English collection, the New Harmonic Magazine (London, 1801). By the early 19th century links with American Methodism had been largely severed in the Maritime colonies and it is not surprising that Humbert would cater to the increasing British presence in the area.

The 4th edition (1840) of Union

Harmony provides a further comment on the state of singing in

Maritime Methodism. In the section entitled "Introduction to the

Grounds of Music," Humbert wrote:

Sounds

on the base should be full, on the tenor bold and manly, (not effeminately, as in the

present practice of

modern times, by females) the counter soft, yet firm, and the treble

smooth and delicate.

Humbert was arguing for a return to the practice of tenors only on the melody. It would appear that the British influence continued to affect congregational singing, so that by mid-century sopranos were beginning to sing melody rather than harmony.

A major influence on Methodist music

was the camp meeting movement. Arising simultaneously in the

British North American colonies and in the United States early in the

19th century, camp meeting music

was fervent and lively judging from extant accounts such as the

following from an 1856 revival at the Peel

and Wellesley mission in Canada West:

They had no instrument, but they could take all the parts of a tune. They had some Old Country music with fugues, and they could all modulate their voices, or sweep in volume that carried all the congregation in one burst of song. (69)

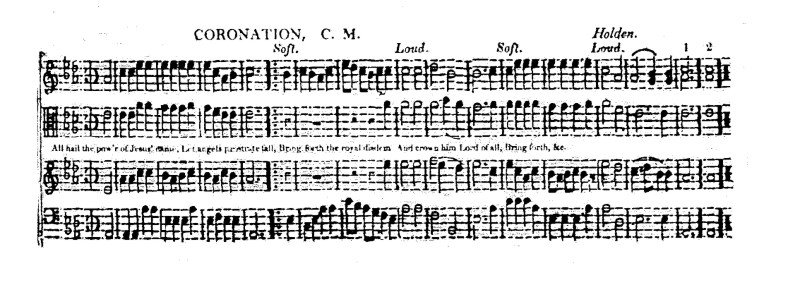

Some camp meeting music was quite complex. (70) The hymn "All hail the power of Jesus' name," to the American tune CORONATION (Example 5), was a long-standing favourite in Canada, both in camp meetings and regular worship. (71)

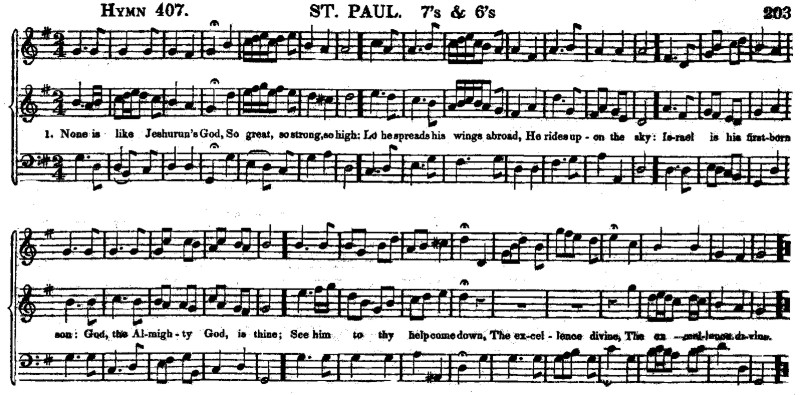

Example 6: ST.

PAUL, from Sacred Harmony

(Toronto, 1838)

Another common feature of camp meeting hymns was the chorus, often

improvised as necessary.

Dorothy Farquharson provides a general description:

They were naive, crude and spontaneously coupled to a hymn. They were catchy, short, rousing and repetitive. The texts were shallow in thought, seldom poetic or overly sentimental, but always vigorous. The words were limited to a few categories: heaven and pilgrimage there, love and praise to Jesus, world rejection, forgiveness and grace. Ejaculations or "shouting words" such as Hallelujah, Save, Yes, Remember Me, and Will You Go were an important part of the refrains. (73)

A hymn of this type, with a nautical flavour popular at the time, is cited by Jane Hopper:The Gospel ship has long been sailing,

Bound for Canaan's peaceful shore;

All who wish to sail to glory,

Come, and welcome, rich and poor.

CHORUS: Glory, glory, hallelujah!

All her sailors loudly cry;

See the blissful port of glory

Open to each faithful eye.

......

Sail with us o'er life's rough sea;

Then with us you will be happy,

Happy through eternity.

CHORUS: Glory, glory, hallelujah!... (74)

Camp meetings were emotional events, filled with fervent preaching, soul-saving, and a good measure of hearty singing.By the 1830s, however, Methodist

singing in Upper Canada had, with exceptions, reached a low ebb. An

editorial in the Christian Guardian lamented:

Time

was when the Methodists were much admired for the melody for the melody

and uniformity of their

singing, but at present it is much to be regretted that a very great

deficiency is apparent among them in this

important part of divine worship; so much so that it has become

frequently the subject of remark: and for our part,

we confess that we would prefer no singing at all, rather than that

which is generally performed in many of our

congregations.

The writer continued:

[An]

evil...exists in the want of uniformity in singing throughout our

extensive Connextion. When tunes are acquired

only by the ear, or through the medium of different publications, it is

quite impossible that all will sing the same

tunes alike; and the necessary consequence is anything but harmony. By

providing a standard work...each members

of our Congregations, wherever he may enter one of our sanctuaries,

will be able to join his fellow-worshippers...in

melodiously celebrating the high praises of his REDEEMER GOD.

Four sample selections from Sacred Harmony were offered to the public in the March 7, 1838 issue of the Christian Guardian (LYDIA, LONDON NEW [Hymnary 646], MOUNT PLEASANT and IRISH [138]), (77) probably representing a cross-section of tunes in use at the time to show potential purchasers of the tunebook that old favourites would be included. Other Methodist tunes mentioned in surviving records include PORTUGAL, DUNDEE, WELLS, CHINA, MEAR, CORONATION, MARTYN, HAMBURG and WEST'S, (78) tunes of wide-ranging origin from both America and Britain with a considerable pre-Methodist influence. A considerable amount of common ground can be seen between this list and that of the Presbyterians at that time.

Sacred Harmony was widely

used throughout Upper Canada over the next 30 years, eventually

reaching 15 editions. (79) The official

sanction of a largely personal collection of tunes had musical

consequences for Canadian Methodism, however. Since 1792 various

editions of the Methodist Discipline

had argued against the singing of fuging tunes in Methodist worship,

yet a sizable selection appeared in

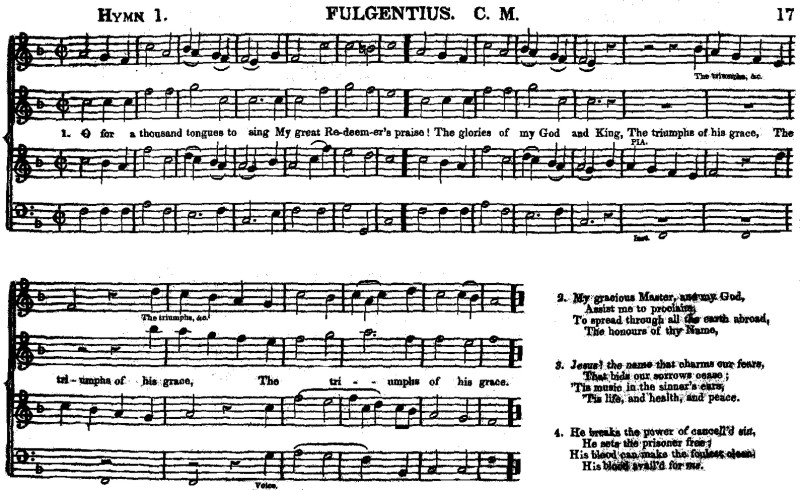

Sacred Harmony. (80) Even "O

for a thousand tongues" was set to a fuging tune, FULGENTIUS (Example

7). (81)

Example 7:

FULGENTIUS, from Sacred Harmony

(Toronto, 1838)

Elaborate Handelian tunes with trills and dynamics are also present

and, in the concluding 15 pages,

figured bass for instrumental accompaniment. Sacred Harmony

may well have encouraged uniformity in

Methodist hymnody, but it also encouraged the growing trend to elitist

professionalism.

Here

it will be seen Sunday is the day for a performance--a performance on a

wind instrument; we are told of

"pedal pipes," and "diaphason pipes"; the instrument is "inferior to

none in the country"; then we hear of

"neighbouring amateurs," of [the organist] showing "high talents," and

of him and his choir "inviting the attention

of the congregation": and all this in a Methodist Church on the Lord's day, when the people are met

to worship God

in spirit. What! are

octaves, and bellows, and fingers, the agency for convicting and

converting sinners? (82)

Similar opinions continued to appear in the pages of the Guardian for years:

Despite such concerns, however, by the 1860s organs and choirs were practically universal in Canadian Methodist worship.

The period after mid-century also witnessed a veritable explosion in Methodist musical publishing activity. The Canadian Church Harmonist was issued in 1864 to replace Sacred Harmony as the official Wesleyan tunebook. (84) A Collection of Hymns (1874) was issued to replace Wesley's own Collection of 1780. (85) The Wesleyan Methodist Hymn Book (1880) and accompanying Methodist Tune Book (1881) were adopted by the larger church after the Methodist union of 1884. (86) Finally the Methodist Hymn and Tune Book was issued in 1894, a combined hymn and tune book in the modern fashion. (87)

As elsewhere in the English-speaking world, the evangelical campaigns of Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey had a tremendous impact on Canadian churches. Sankey's collections Gospel Hymns, Sacred Songs and Solos, and others, sold widely in Canada from the 1870s on. The Methodist Book Room began carrying these collections along with those by other Americans, and issued many of their own. The Dominion Hymnal (1883) was followed by the Canadian Hymnal (1889), (88) later replaced by the New Canadian Hymnal (1916). Other collections include the Canadian Musical Fountain and Revival Singer (1870), the Wave of Sunday School Song (1875), the Great Awakening (1886), and many more. The successor to the camp meeting chorus hymn, gospel song had its greatest impact on weeknight prayer meetings and Sunday evening services. (89)

Two noted Canadian evangelical teams were Crossley and Hunter and the Whyte Brothers. H.T. Crossley edited Songs of Salvation (1887), "as used by Crossley and Hunter, in evangelistic meetings, and adapted for the Church, Grove [i.e. camp meeting], School, Choir and Home." (90) The cover carried a picture of Metropolitan Methodist (now United) Church, Toronto. John M. whyte and D.A. Whyte published three collections: Sing Out the Glad News (1885), Songs of Calvary (1889), and Battle Songs of the Cross (1901). John Whyte was one of the most prolific hymn and tune composers in Canadian musical history, with about 200 to his credit. His texts and music are clearly in the gospel idiom, with vivid imagery and simple harmony such as his "The Dripping of the Blood" and "The Crimson Stream," both from Battle Songs. (91) All four volumes were published and sold by the Methodists.

Congregationalist Church Music in Canada

Few records remain concerning the early development of Congregationalist music in British North America. The diary of Simeon Perkins of Liverpool NS, however, provides one brief glimpse in the entry for February 23, 1777. Perkins speaks of a Mr. Amasa Braman: Spend

the evening at Mr. Joseph Tinkham's singing psalm tunes. I have for

about six weeks attended all the evening

I could conveniently, on a school for that purpose, taught by Mr. Amasa

Braman, a gentleman that came here from

Halifax the beginning of winter. His residence is at Hampstead

[Hempstead], on Long Island. He's a native of

Connecticut, and graduated at Yale Colledge. (92)

Braman did not last long in Nova

Scotia, Perkins noting on April 21, 1778:

It is

reported that Mr. Amasa Braman, who has resided here about 16 months,

is absconded, and gone off this

morning.... This Mr. Braman came here from Halifax, and says he belongs

to Long Island. Has kept school, and

taught singing, and practised the Law. He is gone away in debt.

Braman did leave one musical legacy.

Perkins records the results of an important congregational meeting

shortly before Braman left:

Thursday, March 19th, 1778,--... We have a meeting concerning coming

into some regulations about singing in

the Congregation. We voted to sing without reading, and choose 4

gentlemen to lead on the tenor, viz. Deacon Nath

Freeman, Nathan Tupper, junr., Perez Tinkham, John Nickerson. On the

bass, Joseph Tinkham, Lothrop Freeman,

Joseph Freeman, Peleg Freeman. (93)

Lining out was abandoned in favour of choral leadership, a practice that was to become increasingly common over the years.

The next Congregationalist reference comes almost 70 years later. A broadsheet of hymn texts published for the opening of Zion Congregational, Montreal (February 8, 1835) provides a typical cross-section of hymns by Watts and others but without indicating tunes. (94) When Congregationalist newspapers began publishing in the 1840s and 50s, choirs are mentioned frequently enough to suggest they were already fairly common. (95) Organs were in place in Carleton PEI in 1842, (96) First Congregational, Toronto, 1855, (97) and a new organ in Brantford ON in 1866 replaced a melodeon in use "for several years past." (98) By the 1870s organs were undoubtedly quite common.

Other musical aspects receive notice during the 1860s and later. Plans for the reform of psalmody flourished for a time in the leading churches of Toronto, including changes in congregational singing practices and the use of a numeric notational system. (99) By this time it seems that the British influence had prevailed and the melody is assumed to be in the soprano. (100) Organs and melodeons were generally accepted as beneficial in leading singing. (101) Despite attempts at reform, however, the practice of having a minister or precentor read the hymn before singing was still relatively common, though by now more a custom than a necessity. (102) Tunes mentioned in the Canadian Independent that appear to be well-known in Congregational churches include: GREENVILLE, CORONATION, OLD 100TH, DUNDEE, MELCOMBE (Hymnary 207), ST. ANN'S, BOYLSTON, ARNOLD (645), BALERMA, MARINERS (304), PISGAH, PORTUGUESE HYMN (ADESTE FIDELES, 47), SILVER-STREET, ANTIOCH (55) and HARWELL. Many of these appear in the context of examples of old tunes to be avoided or treasured tunes now gone. (103)

With a few minor exceptions Canadian Congregationalists did not publish hymn collections. (104) By the 1850s churches were using a variety of books with little uniformity. (105) Two collections eventually prevailed: the American Sabbath Hymn Book and the British New Congregational Hymn Book (1859). (106) Late in the century a British revision was issued, the Congregational Church Hymnal (1887). A concerted effort was made at the conference level to introduce this hymnal in all congregations, with a considerable measure of success. (107) By the time of union in 1925 it was in use in the majority of Canadian Congregational churches.

The Twentieth Century

By 1925 organs and choirs were firmly entrenched in Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational worship, to the point that people could scarcely remember otherwise. (108) The "cathedral" churches of these denominations were among the leading centres of music in the country, with elaborate music programs involving multiple choirs, orchestras, quartettes and soloists. (109) Evening services, especially, had become virtual musical concerts. (110) Even smaller churches were capable of regularly employing special music in worship. (111) Curiously, in spite of the impetus

towards church union, both the Methodists and Presbyterians

chose to revise their hymn collections during the First World War. The Methodist

Hymn and Tune Book was

published in 1917, the Presbyterian Book of Praise in 1918.

Some members felt that they could not wait

for union, that a new hymnal was needed immediately:

We

welcome this decision [to revise the Hymn and Tune Book] from the bottom

of our hearts, for we believe it to

be altogether in the interests of our church. There has been long delay

in this matter, owing to the proximity of

church-union, we are told. There is great cause for satisfaction that

in the meantime we are to set our own house

in order as fully as possible. (112)

By the early 20th century the three denominations shared a considerable common repertoire of hymns and tunes. Though a union hymnal had been proposed, and the Presbyterian and Methodist committees did meet jointly, the differences between the two traditions proved to great to bridge:

The 1917 Methodist and 1918 Presbyterian books had 357 hymn and psalm texts in common (out of 656 for the Methodists and 809 for the Presbyterians), (114) yet the Presbyterian committee concluded that "should a united church be the result of the present negotiations it will require a number of years of interchange and development of church life together before one common book representing the whole people could be prepared." (115) Indeed, denominational loyalties continued to plague the United Church committee as it compiled the 1930 Hymnary. (116) It would be many years before the members of the new church truly felt "united" in matters of hymnody. Perhaps if the Presbyterians and Methodists and waited just a bit longer, this problem might, at least partially, have been alleviated.

Patterns of church music in the three founding denominations of The United Church of Canada changed radically over the course of a relatively brief span of time. Beginning with strong denominational traditions, the three churches shared, by the time of union, many hymns and tunes in common, and choirs and organs had become almost universal. The Canadian churches were not alone in this revolution. Changes in Canadian church music followed those of the United States and Great Britain, the powerful influence of the American churches resulting from the Loyalist immigration during the late 18th century gradually being replaced by British influence during the successive waves of emigration from the "old country" in the first half of the 19th century. American influence continued, however, particularly in the gospel hymn movement and the development of the reed organ.

Presbyterian practices changed the most, Presbyterians moving from a vociferous anti-instrument, psalms-only tradition to becoming a major force in Canadian musical life. Yet all three denominations sacrificed much of their heritage. All three had begun as protestant (as in protesting) churches, who wished to return to a simpler musical tradition with the congregational voice central in the praise of God. Over the years, however, the concern for the quality of music in worship gave rise to a much more professional approach to church music, with choirs and organs prominent and congregations largely abdicating their responsibility in praise. We can hardly imagine worship today without church musicians. One wonders, however, whether we are not missing out on the glorious sound of a cappella voices united in sacred song.

1. In later psalters separated into four lines (8686) and known as Common Metre.

2. The radically different natures of these translations can be seen in the following examples from Psalm 23:

Tate

& Brady 1696

The Lord himself, the mighty

Lord,/vouchsafes to be my guide;

The shepherd, by whose constant

care/my wants are all supplied.

3. There is a striking similarity between WINCHESTER OLD and a section (chapter 8, second half, treble part) of Christopher Tye's Acts of the Apostles (1553), a common metre translation and simple musical setting of a portion of the book of Acts (cf. Maurice Frost, English and Scottish Psalm and Hymn Tunes c. 1543-1677 [London: Oxford University Press, 1953] #103 and #302). Other psalm tune phrases appear in this work suggesting a common melodic vocabulary in use at the time. Nicholas Temperley has suggested that some psalm tunes may have originated as harmonies to other tunes (cf. Temperley, "The Old Way of Singing," Journal of the American Musicological Society 34 [1981] 529-32).

4. Cf. Erik Routley, The Music of Christian Hymnody (London: Independent Press, 1957) 46. GLASGOW TUNE appears to have fallen into disuse.

5. The Hymnary of The United Church of Canada includes ABBEY (652), DUNDEE (652), DUNFERMLINE (40), FRENCH (176), MARTYRS (668) and YORK (630).

6. This collection was the first music published in North America.

7. Misnamed as the 115TH PSALM TUNE, an error that appeared in the English source for this collection, John Playford's A Brief Introduction to the Skill of Musick (1654). Cf. Richard Appel, The Music of the Bay Psalm Book, I.S.A.M. Mono-graphs 5 (New York: Institute for Studies in American Music, 1975) 4.

8. Cf. Hymnary: OLD 100TH (6), OLD 113TH (10), ST. DAVID'S (674), ST. MARY'S (127).

9. These early tunes have a number of features in common. Written in the old modal system which preceded tonality, many defy categorization according to major or minor key (cf. MARTYR'S). Angular melodic contours and wide ranges are common (cf. ST. DAVID'S and ST. MARY'S). Although altered over the years to conform with changing conceptions of rhythm, many of the tunes in their earlier forms defy attempts to interpret them according to strict metrical concepts.

10. For a detailed discussion cf. Temperley, "The Old Way of Singing" 511-44.

11. William Taas, The Elements of Music (Aberdeen, 1787) 34, cited in Temperley, "The Old Way" 523. As psalm tunes were normally printed in a combination of whole notes and half notes (a whole note actually equalling our half note), this was a slow pace indeed!

12. Robert Rennie describes this practice: "[An interesting characteristic of Presbyterian psalmody was] the precentor's practice of 'gracing' the singing of the psalm through the addition of unauthorized shakes and quavers to the tune very much as the spirit moved him. Such ornamentation was copied in turn by the congregation at will, and the result must have been sheer cacophony. The tune was hardly identifiable amid the graces that smothered it, although many precentors tried to protect themselves through displaying the name of the tune boldly, if rudely, printed on a cardboard set in front of their desks" (cf. Rennie, "Spiritual worship with a carnal instrument: the organ as an aid or obstacle to the 'purity of worship' in Canadian Presbyterianism, 1850-1875," M.Th. thesis, Knox College [1969] 57).

13. "Of

Singing of Psalms," A Directory

for the Publique Worship of God

Throughout the Three Kingdoms of

England, Scotland, and Ireland (1644).

14. In light of the fact that the Scottish

delegates at Westminster had actually

opposed of lining out, it seems ironic

that the practice continued so much

longer in Scotland than in England.

15. Four

Centuries of Scottish Psalmody (London: Oxford University Press,

1949) 130. 16. The Gamut was a widely-used

system found in many tunebook

prefaces which involved teaching

people to sing by using four

solmization syllables: mi fa so la. In

this system a C major scale (C D E F

G A B C) would be rendered fa so la

fa so la mi fa. This system was

thought to be simpler to understand

than the hexahordal system (ut [do] re

mi fa so la) in use in continental

Europe at the time (cf. Robert

Stevenson, Protestant Church Music in

America [New York: W.W. Norton &

Co., 1966] 21).

17. Cf. Stevenson 21-31.

18. The formation of church choirs was

a direct result of this movement.

19. Cf. Nicholas Temperley, "The

origins of the fuging tune," Royal

Musical Association Research

Chronicle 17 (1981) 1-32.

20. Temperley and Charles Manns,

Fuging Tunes in the Eighteenth

Century (Detroit: Information

Coordinators, Inc., 1983) viii.

21. Richard Crawford, The Core

Repertory of Early American

Psalmody, Recent Researches in

American Music 11 and 12 (Madison

WI: A-R Editions, 1984) xli.

22. The Choir (Halifax, 1887) is the

last

Canadian book I have found to

contain fuging tunes.

23. "The Preface,"Hymns and Spiritual

Songs (London, 1709), reprinted in

Selma L. Bishop, Isaac

Watts: Hymns

and Spiritual Songs 1707l-1748

(London: Faith Press, 1962) lii-lv. 24. Of the 45 pieces included, over half

are by Watts and his follower, Phillip

Doddridge (cf. Louis Benson, The

English Hymn: Its Development and

Use in Worship [Richmond VA: John

Knox Press, 1915] 148).

25. Known hereafter as the Scottish

Paraphrases. Famous examples of

texts from this collection can be found

in the Hymnary 54, 60, 269, 446.

26. Benson 150.

27. Select hymns with tunes annext

(London, 1761) was Wesley's definitive

tune collection. A list of instructions

for congregational singing appears on

the final page.

28. Wesley wrote in his journal (August

9, 1768): "I began reading prauers at

six, but was greatly disgusted at the

manner of singing; (1) twelve or

fourteen persons kept it to themselves,

and quite shut out the congregation;

(2) these repeated the same words,

contrary to all sense and reason, six or

eight times over; (3) according to the

shocking custom of modern music,

different persons sung different words

at one and the same moment; an

intolerable insult on common sense,

and utterly incompatible with any

devotion" (cited in Fred Graham,

"John Wesley's choice of hymn

tunes," The Hymn 39.4 [October 1988]

30).

29. Cited in the Oxford Companion to

Music (10th edition, 1970) 631.

30. Cited in James Warren, O for a

thousand tongues to sing (Grand

Rapids, Michigan: Francis Asbury

Press, 1988) 74.

31. This collection was edited by John

Frederic Lampe rather than Wesley,

the more elaborate nature of the music

probably reflecting Wesley's lack of

editorial control.

32. Commonly known as Sacred

Melody, this collection was re-issued

in a harmonized version as Sacred

Harmony in 1780.

33. Nicholas Temperley, "Stephen

Humbert's Union

Harmony, 1816" in

Sing out the glad news: hymn

tunes in

Canada, CanMus Documents 1

(Toronto: Institute for Canadian

Music, 1987) 82. 34. A crochet is the British term for a

quarter note.

35. William Billings (1746-1800) and

Oliver Holden (1765-1844) were well-known American composers of fuging

tunes and anthems.

36. Reprinted in "Old Fashioned

Singing," The World of Music

(Claremont NH) 4.24 (1847) 94.

37. Jane Hopper, Old-Time Primitive

Methodism in Canada (1829-1884)

(Toronto: William Briggs, 1904) 76.

The connection between the Hopper

and Boston Courier citations is made

by Stephen Blum in "The fuging tune

in British North America," Sing out

the glad news 119-20.

38. Reprinted in the Christian Guardian

(9 January 1830) 64. 39. Cf. Richard Crawford, "'Ancient

Music' and the Europeanizing of

American Psalmody, 1800-1810" in A

Celebration of American Music (Ann

Arbour: University of Michigan Press,

1990) 225-55.

40. The Canadian Church Harmonist

(Toronto, 1864) lists Mason along

with composers such as Handel,

Haydn and Mozart on its title page.

41. Cited by Edith Firth in The Town of

York, 1793-1815, Publications of the

Champlain Society 5 (Toronto:

Champlain Society, 1962) 248. 42. Cf. Richard Crawford, "Preface," in

James Lyon, Urania (reprint of 1761

edition, New York: Da Capo Press,

1974) i-iii.

43. The British vertical-octavo format,

with the melody in the treble,

prevailed after mid-century. Cf. John

Beckwith, "Introduction," Hymn

Tunes, Canadian Musical Heritage 5

(Ottawa: Canadian Musical Heritage

Society, 1986) vii. 44. Cf. Crawford, "Preface," Urania

xxix-xxxv.

45. Collections specific to a particular

denomination are a later phenomenon;

in Canada, principally after 1850.

46. In a section entitled "Of the Graces

in Music" in the Theoretical

Introduction, and echoing the

instructions of John Wesley, Lyon

advocates a more conservative

approach to psalm tunes than to other

music: "The Trill or Shake is used on

all descending prickt Crotchets; on the

latter of two Notes on the same Line

or Space; and generally before a

Close. The other Graces are seldom

used in plain Church-Tunes, but are

very proper in Hymns & Anthems."

Even following these instructions,

however, psalm tunes would contain a

fair number of trills.

47. Found in the Collection of the

Norfolk County Historical Society,

Eva Brook Donly Museum, Simcoe

ON.

48. The foregoing section based on

Dorothy Farquharson, "O for a

thousand tongues to sing": a history of

singing schools in early Canada

(Waterdown ON: published by author,

1983) 45-48. Facsimiles of SAVOY

and MARTYR'S from this book are

printed in Beckwith, Hymn Tunes, 6c

and 8d.

49. John Howison, Sketches of Upper

Canada (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd,

1821) 134-5. 50. (24 January 1828). Mackenzie

added the following comment:

"Without intending any reflection

upon the very respectable and

exemplary young gentlemen who

guide the music, we may say, that if

they would now and then substitute

Dundee, Elgin, Martyrs, St. Davids,

Irish, Portugal, Stroudwater, the old

hundred, or any other well known

plaintive or solemn air in place of the

jig and strathspey measures with

which they regale 'The Fancy,' one

very considerable portion of the

congregation would feel greatly

obliged" (cf. the Hymnary

632 for

STROUDWATER). 51. MacKenzie mentions an organ in

the American Presbyterian Church,

Montreal, in 1831 (cited in Rennie 71,

following Robert Campbell, A History

of the Scotch Presbyterian Church, St.

Gabriel Street, Montreal [1887] 752).

52. Between 1840 and 1858, 39 patents

for reed organ technology were issued

by the US Patent Office, including an

1856 patent on mass-production

techniques (cf. Barbara Owen, "Reed

Organ," New Grove Dictionary of

Musical Instruments [1980] 222-3).

53. Cf. Rennie 75. The intense emotions

raised by the issue are epitomized by

the following account of the

immediate pre-organ days in

Brockville: "It being utterly impossible to secure an organ, the best

substitute was a bass viol. On Sunday

the hymn was given out when, to the

horror of one of the elders, there arose

the loud and clear notes of what he

considered an enormous fiddle. Rising

from his pew he proceeded in great

haste to the gallery, grasped the bow

from the hands of the astonished

musician, breaking it across his knees

and at the same time muttering, 'We'll

have nane of the devil's playthings in

the House of God'" ("A

Congregational History, First

Presbyterian Church, Brockville"

[1966], cited by Rennie 70).

54. Alexander Kemp, Digest of the

Minutes of the Synod of the Presbyterian Church of Canada

(Montreal:

John Lovell, 1861) 63. 55. Cf. Kemp 64-6.

56. Two important pamphlets are The

organ question: statements...for and

against the use of the organ in public

worship, in the proceedings of the

Presbytery of Glasgow, 1807-08

(Toronto: Lovell & Gibson, 1859) and

George Christie, The use of instrumental music in the public

worship of

God (Halifax: James Barnes, 1867).

57. Cf. The Presbyterian (Montreal,

March 1966) 67: "If the organ will

remedy this state of things [the lack of

singing in worship], by all means let

us have it.... If, on the contrary, an

organ, or a choir, is to usurp the place

of the congregation, is to be made

means of showing off how elaborately

and artistically the Psalms or Hymns

of our Church can be trilled forth in

the ears of the people, listening to

voices from an organ loft as they

would to an opera, then banish both.

Better the rudest accents of praise

from the lips of the most uncultured

than this pretence."

58. Cf. Rennie 205-8.

59. Cf. Thomas Harding 25-6 for

further dates and information.

60. The United Presbyterians were the

most liberal in the matter of hymnody.

Eventually, however, all three

branches of Scottish Presbyterianism

issue definitive hymn collections: the

Church of Scotland's Scottish Hymnal

(1871), the United Presbyterian's

Presbyterian Hymnal (1877), and the

Free Church Hymn Book (1882).

61. 8.3 (January 1853) 42.

62. Cf. 1 (November 1857) 297.

63. Cf. N.Keith Clifford, "The contribution of

Alexander MacMillan to

Canadian Hymnody" in William

Klempa ed., The burning bush and a

few acres of snow: the Presbyterian

contribution to Canadian life...

(Ottawa: Carleton University Press,

1994) 159-81.

64. Clifford (p.161) cites MacMillan's

United Presbyterian (i.e. liberal,

Anglican-influenced) background,

together with his exposure to the

Oxford Movement while in Scotland

in 1894, as the major causes of his

catholic and liturgical biases

throughout his career in Canadian

hymnody.

65. "Congregational Singing," Canada

Christian Advocate 23.43

(November 6, 1867). 66. A foreign observer noted, however:

"The inconsiderate habit...of singing

hymns and psalms upon almost every

occasion.... In Canada, the custom

even more generally prevails, and is

practised among almost every

religious persuasion; though I find by

the methodistical part of the

community its observance is

appropriated to a larger share...than by

any other. The stranger, who is not

accustomed to a continuous series of

psalm singing, must not take for

granted that...such is practised, either

for the express purpose of communing

with the spiritual Author of all

consolation, or sounding the depth of

His praises on high, for such is not in

anywise the case; the music appertains

solely to...the lessening of bodily

inconveniences... compelling the

resources of the mind to take share in

the burthen of the operations. The

furrowed frill that binds the fair neck

of the lady cannot be laid across the

symmetrical restrictions of the italian

iron without an hymn--the

gesticulations of the churn-dash are

ineffectual without an

incantation--and the querulous sigh

of the bellows, resigns its claim upon

ignition, bereft of doxology" (C.H.C.,

It Blows, It Snows [Dublin: P.W.

Brady, 1846] 135-6).

67. Cf. Barclay MacMillan, "Tune-book

imprints in Canada to 1867: a

descriptive bibliography," Papers of the

Bibliographic Society of Canada 16

(Toronto, 1978) 46-8. Union Harmony

must have received a wide reception as

James Dawson, a Pictou NS singing

master, referred to it in the

advertisement for his own projected

Harmonicon in 1832: "The collection

of Church Music called the Union

Harmony, having long been out of

print, is now exceedingly scarce. The

subscriber, under the impression that a

new publication, embracing all the best

Tunes of that excellent collection,

together with a judicious selection from

the other books of similar character is

much wanted, proposes publishing such

a work, as soon as the number of

subscribers shall be such as to

indemnify him for the expense"

(Yarmouth Telegraph [January 20,

1932] 4). Although Dawson did not

receive enough subscriptions to publish

his own volume until 1836, the third

edition of Union Harmony appeared in

1832.

68. This discussion follows Temperley,

"Stephen Humbert's Union Harmony,

1816" in Sing Out the Glad News 78-84.

69. Hopper 213 (cf. Dorothy

Farquharson, "Camp Meetings: their

history and song," 70. A Selection of Camp-meeting and

Revival Hymns (Stratford ON, 1863)

includes a hymn called "Camp

Meeting" to the tune LENOX. The

hymn vividly describes the camp

meeting singing experience (cf.

Farquharson 81).

71. This hymn and tune are mentioned

in a camp meeting description in

William Withrow, Life in the

Parsonage (cited in Farquharson 72-3). The text and tune are still

found

together in the Hymnary 46 (alternate).

72. From the Canadian tunebook Sacred

Harmony (cf. Farquharson 78, quoting

from John Carroll, Case and His Co-Temporaries [1867]). This

is not the

same tune as ST. PAUL in the

Hymnary.

73. Farquharson 76.

74. Hopper 206-7.

75. (May 5, 1833) 118-19.

76. Cf. J.William Lamb, "Canadian

Methodism's first tunebook: Sacred

Harmony, 1838" in Sing out the glad

news 91-118 for a general study of

Sacred Harmony and its mileau.

77. The first two were published in

standard musical notation, the second

two in shaped-note notation,

representing the two different editions

of Sacred Harmony being offered.

78. Cf. Guardian (December 1, 1847)

26, (February 4, 1857) 69, (September

24, 1873) 308, and Hopper 104-5.

79. John Beckwith (Hymn Tunes 43)

estimates that 10,000 copies of Sacred

Harmony were printed, Lamb (p.118)

suggests a figure as high as 30,000!

80. The relevant section was: "15. The

preachers are desired not to encourage

the singing of fuge tunes in our

congregations. 16. We do not think

that fuge tunes are sinful, or improper

to be used in private companies: but

we do not approve of their being used

in our public congregations, because

public singing is a part of divine

worship, in which all the congregation

ought to join" (The Doctrines and

Disciplines of the Wesleyan methodist

Church in Canada [Toronto, 1836] 68-9).

81. One of four tunes included for this

hymn.

82. (August 17, 1842) 170.

83. (September 24, 1873) 308, quoting

from the Pittsburg Advocate. 84. David's theoretical introduction was

largely retained, although fuging tunes

played a much less prominent role.

LENNOX, for example, was reduced

to a homophonic setting (compare

Example 8 with Example 1):

85. The book contains words only, but

with an index suggesting suitable

tunes for each text.

86. The Tune Book was the first

Canadian Methodist tunebook in the

British octavo format, with four parts

on two staves and melody on top. The

fuging tune was virtually eliminated,

with RUSSIA (Example 9) retaining

only a vestige of its fuging nature, for

example:

87. The hymns remained the same as in

the 1880 book; the tunes, however,

were revised.

88. Revised and enlarged in 1901.

89. First Congregational Church in

Ottawa voted to adopt a Moody and

Sankey collection for its Sunday

evening services in 1886 (cf. the

Congregational Record 1.4 [February

1886] 2). A month later it was

reported that: "The adoption of the

Sankey collection of hymns at the

Sunday evening services has proved a

success. The attendance has been

larger and the singing heartier. The

congregation is always best pleased

when it can join readily in every piece

that is being sung" (Record 1.5

[March 1886] 2).

90. Title page.

91. The Whytes had a degree of

international fame. The 1890 edition

of the popular American collection

The Finest of Wheat (the title page lists

it as the 54th edition!) includes "the

Whyte Brothers of Canada" among

the list of evangelists for which it was

compiled, in company with such

famous American evangelists as

William J.Kirkpatrick (copy in

author's personal collection).

93. p. 186.

94. Montreal-Ottawa Conference

Archives (The United Church of

Canada), Zion Congregational Church

Fonds (7/z10/12/1).

95. Cf.

"Russeltown--Ordination--Formation of a Christian Church," The

Harbinger 1.8 (Montreal, August 15,

1842) 115; Robert Young, "Piety in

Church Choirs," Harbinger 2.5 (May

15, 1843) 68.

96. Although not in a proper meeting

house (cf. H. Wilkes, Letter to the

Harbinger 1.11 [November 15, 1842]

163-6).

97. "First Congregational Church,

Toronto," Canadian Independent 1.17

(March 5, 1855) 133.

98. "New Organ at Brantford,"

Independent 13 (1866/67) 225-6.

99. "Two plans for church music,"

Independent 13 (1866/67) 149-55,

205-7.

100. Judging from the musical examples

provided and the following comment:

"Undoubtedly, if our object was to

form a choir only, we must reject

every male voice from the number of

those who sing the melody" (p.150).

101. Pp.152, 154.

102. Cf. W.F.C., "The psalmody fever,"

Independent 13 (1866/67) 244.

103. List compiled from 1.6 (October 2,

1854) 47; 13 (1867) 78, 206-7; 14

(1867/68) 319; 25.10 (March 13,

1879) 4; 29.32 (February 10, 1881) 2-3. OLD 100TH, DUNDEE (or

FRENCH) and BOYLSTON appear

most frequently.

104. Church Psalmody (Quebec, 1845)

was compiled by direction of the

Congregational Union of Eastern

Canada and contained selections from

"Dr. Watts's Psalms and Hymns and

the Congregational Hymn Book," both

of which were difficult to acquire (cf.

Preface). A later collection, Hymns of

Praise (Montreal, 1873), was compiled

and issued by a committee from Zion

Church. It was published in at least two

editions but seems to have been

adopted only in Quebec (cf. the

Independent 19 [1872/73] 8-10, 400; 20

[1873/74] 60; 21 [1874/75] 94).

Neither book seems to have survived

for long.

105. Cf. the Independent 5

(1858/59)

297: "Many [churches] are dissatisfied

with the book, or books, now in

use;...new churches feel a difficulty in

making a selection from the many

rival claimants, new and old, for their

favour.... The Presbyterian or

Wesleyan, wherever he goes, is sure

to find the same book of Psalmody in

use among his brethren. We would it

were so with us."

106. Cf. the Independent 19

(1872/73) 8.

107. Cf. the Congregational Record

1.5

(June 15, 1892): "During the Union

meetings Mr. Thacker, representing

the Congregational Union of England

and Wales, showed the various

editions of the new 'Congregational

Hymnal,' and urged its use. Several

ministers who are using it spoke

highly in its favour, and a resolution

was passed recommending it to the

churches. This is the hymn book we

[Calvary Church, Montreal] have just

voted to adopt" (Montreal-Ottawa

Conference Archives, Westmount

Park United Church Fonds

[7/WES/33/5).

108. The minister of Emmanuel

Congregational, Montreal preached a

quite remarkable sermon in 1908 on

"The Religious Value of Music":

"...[the organ] is unique in its capacity

of speaking to the deeper, higher

elements in the soul of man. Now it is

quite possible for an organist...to play

in such a manner at the opening of a

service that, however worried men

and women may be as they come to

church the sweet, solemn, inspiring

strains of the organ will...hush and

quiet the soul." "[If] it is possible for

one man--the minister--to voice the

prayer of a congregation," he argued,

"why should it not be possible for a

body of singers to express the praise

of a congregation? ... A choir of the

right sort can and may be the

mouthpiece of the congregation in

pouring out its sorrow, its joy, its

petitions, and its praise..."

(cf. Emmanuel Church Outlook 1.11

[December 1908] 4 in the Montreal-Ottawa Conference Archives,

Westmount Park United Church

Fonds [7/WES/15/4]). 109. According to an article in the

Conservatory Quarterly Review (1.1

[November 1918] 19), nine of the 12

"Notable church and concert organs of

Toronto" were in Presbyterian and

Methodist churches.

110. An order of worship for January 5,

1913 (evening service) at Grace

Methodist, Winnipeg lists an amazing

15 hymns, an organ solo, anthem, two

vocal solos, two duets, two male

quartets, a [mixed] quartet, a chorus,

and a "duet and chorus." Time was

even found for prayer, scripture,

sermon and offering (the order does,

however, mention that this was a

special service) (cf. Manitoba Conference Archives [Winnipeg] Grace

Church Fonds, file "Selected service

bulletins" [F.4, Box B]).

111. Some of the earliest Presbyterian

services in Fort George [Prince

George] BC were enhanced by an

organ and choir or quartette (cf.

British Columbia Conference

Archives: The records of Knox United

Church, Prince George BC, Record of

Services [1910-1913], handwritten

volume).

112. "A new Methodist hymn-book," Grace Church Bulletin 1.8 (April

1911) 1 (Manitoba Conference

Archives, Grace Church Fonds [F.4,

Box B]). 114. Clifford 162.

115. Acts and Proceedings (1915)

253.

116. For the controversies involved in

the Hymnary process see Thomas and

Bruce Harding, Patterns of Worship in

the United Church of Canada, 1925-1960, Chapter 2 and Clifford

165-71.